Main Buliding

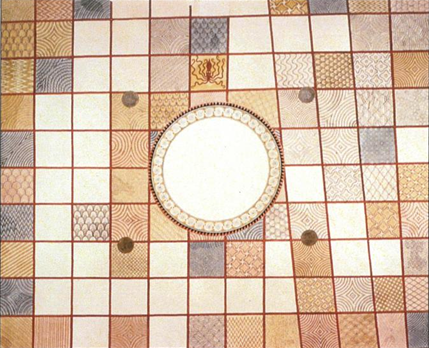

The throne itself was made of perishable material, probably wood, no doubt decorated with ivory or other inlaid work. This spacious hall, 12.90 m long and 11.20 m wide (42.3 χ 36.8 feet), was bright with multicolored painted decoration. The floor was laid out in squares (Fig. 7), each bearing linear patterns in red, yellow, blue, white and black, and perhaps other colors. Only in front of the throne was there a somewhat realistic representation, of a huge octopus.

The hearth was also adorned with painted patterns (flames, notches, and spirals) on the riser, a narrow ledge, and the broad border that surrounded the place for the fire. Near the hearth, beside the western column base, stood a clay table of offerings, coated with stucco. The columns, with their thirty-two flutes, and all the woodwork of ceiling and balcony were no doubt brightly painted. All four walls were covered with frescoes. A preserved fresco of a lion and griffin comes from the wall to the left of the throne; it was probably matched by another pair to the right.

The hearth was also adorned with painted patterns (flames, notches, and spirals) on the riser, a narrow ledge, and the broad border that surrounded the place for the fire. Near the hearth, beside the western column base, stood a clay table of offerings, coated with stucco. The columns, with their thirty-two flutes, and all the woodwork of ceiling and balcony were no doubt brightly painted. All four walls were covered with frescoes. A preserved fresco of a lion and griffin comes from the wall to the left of the throne; it was probably matched by another pair to the right.

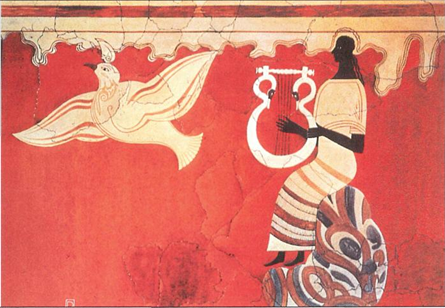

Farther to the viewer's right on the same wall was a banquet scene, perhaps the culmination of a procession of men and women leading a bull to sacrifice, which begins in room 5. One of the most evocative fragments shows a male figure seated on a rock and playing a lyre (Fig. 8).

Beside the throne, at the king's right, is a curious installation—a shallow basin-like hollow in the floor—from which a narrow V-shaped channel leads to a second slightly lower hollow some 2 m (6.5 feet) distant. It might have been a convenience to permit the king, without getting down from his throne, to pour out libations to one or another of the gods, a ceremony often mentioned in the Homeric poems.

The many open slots and grooves visible in the walls surrounding the throne room once contained the great ver¬tical and horizontal beams which in Mycenaean architecture made up the sturdy framework of the walls. Originally the beams may have been left visible in the face of the wall, more-or-less in the fashion of the half-timbered style in England; but in the later phases of the palace the timbers were all covered over with plaster and could not be seen. It is obvious that the wooden beams contributed much to the intensity of the fire that destroyed the palace and turned so many of its stones into lime.